Think Smart About Sparse Compute: LatentMoE for Higher Accuracy per FLOP and per Parameter

Published:

Read the Paper

Authors: Venmugil Elango, Nidhi Bhatia, Roger Waleffe, Rasoul Shafipour, Tomer Asida, Abhinav Khattar, Nave Assaf, Maximilian Golub, Joey Guman, Tiyasa Mitra, Ritchie Zhao, Ritika Borkar, Ran Zilberstein, Mostofa Patwary, Mohammad Shoeybi, Bita Rouhani

Sparsity ≠ cheap inference

Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) is often pitched as “activate a few experts, get a lot of parameters for cheap.” That framing is mostly about FLOPs—but serving doesn’t care only about FLOPs.

In real deployments, MoE cost is frequently dominated by memory movement & communication:

- Interactive serving (low latency): streaming expert weights from HBM dominates latency when few tokens hit each expert.

- Throughput serving (scale-out): all-to-all routing dominates when token vectors must move across GPUs.

For an optimal design, one should answer the following question:

⇒ How much accuracy do we get per byte moved and per FLOP spent, under realistic serving constraints?

LatentMoE is built around this question.

LatentMoE: A serving-aware MoE

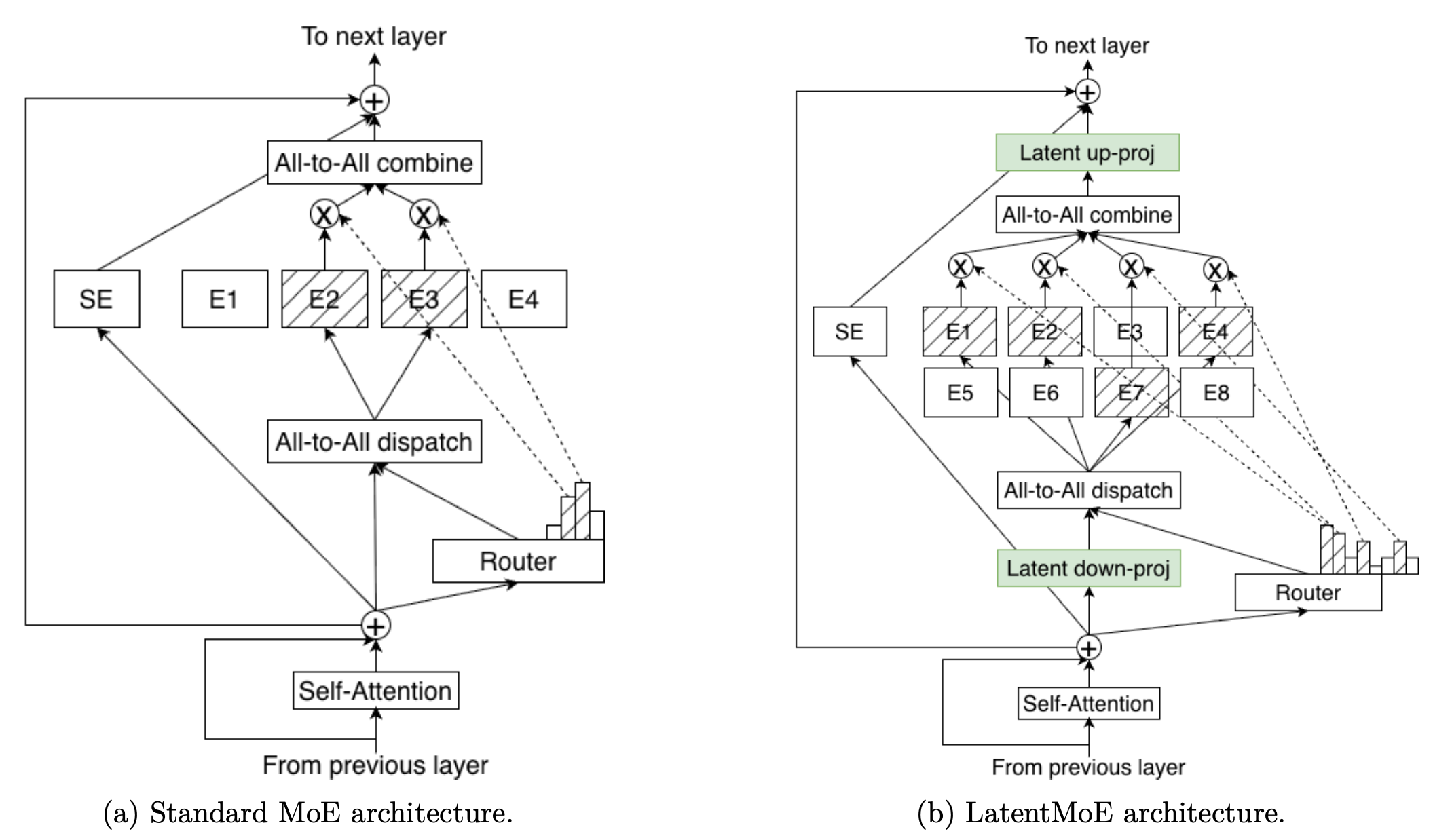

LatentMoE is a revised MoE architecture that improves accuracy per parameter and per FLOP by making the routed expert path cheaper (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (a) Standard MoE: routing payloads and routed expert compute operate in hidden dimension d. (b) LatentMoE: project to latent dimension ℓ for routing payloads and routed expert compute, then project back to d. This reduces both routing bytes and expert weight bytes by roughly d/ℓ. The savings are reinvested into more experts and higher top-k at similar serving cost, improving expressivity and combinatorial sparsity.

Figure 1. (a) Standard MoE: routing payloads and routed expert compute operate in hidden dimension d. (b) LatentMoE: project to latent dimension ℓ for routing payloads and routed expert compute, then project back to d. This reduces both routing bytes and expert weight bytes by roughly d/ℓ. The savings are reinvested into more experts and higher top-k at similar serving cost, improving expressivity and combinatorial sparsity.

Instead of running routed experts on the model’s hidden representation, LatentMoE wraps the routed path with two shared linear layers:

- Project tokens down to a smaller latent representation (d → ℓ) before dispatch

- Perform expert dispatch/combine and expert compute in that latent space

- Project expert outputs back up to the model’s hidden representation (ℓ → d)

Importantly, the router still computes gating decisions from the model’s hidden representation—only the routed payload and routed expert computation move into the latent space. Shared experts, if present, operate in the original hidden dimension.

By shrinking what must be moved across GPUs and what expert weights must be read per token, LatentMoE reduces both memory traffic and all-to-all routing volume.

It reinvests those savings into a larger number of experts and higher top-k, improving model accuracy at roughly similar serving cost.

LatentMoE has been adopted in NVIDIA’s Nemotron-3 Super and Ultra family.

Design Principles Behind LatentMoE

LatentMoE takes a hardware-software codesign approach. It was guided by five principles:

-

Low-latency inference is memory-bound. In low-latency serving scenarios, MoE inference is often dominated by the memory bandwidth cost of reading expert weights. As a result, accuracy per parameter matters for interactive applications, since parameter footprint largely determines how much weight data must be moved.

-

High-throughput inference is communication-bound. In throughput-oriented serving, distributed MoE inference is dominated by all-to-all routing. Routing volume scales with tokens × top-k × routed width. Consequently, communication overhead can be mitigated by reducing the routed width.

-

Preserve nonlinear capacity. Model quality tracks the effective nonlinear budget per token: top-k × expert intermediate dimension. Consequently, to alleviate memory and communication bottlenecks without sacrificing model quality, we should keep both top-k and expert intermediate dimension unchanged.

-

Don’t over-compress features. There is a task-dependent “feature rank” that imposes a lower limit on the reduction of hidden dimension d to latent dimension ℓ. Reducing below this limit degrades model quality.

-

Exploit combinatorial sparsity. MoE gains come from expert specialization. Increasing both the number of experts and top-k expands the space of expert combinations dramatically, which can improve accuracy.

These principles led to a clear strategy:

- Shrink the routed width: compress hidden dimension d to latent ℓ, keeping top-k and expert width intact—to cut dominant serving costs without sacrificing accuracy

- Respect the compression floor: don’t shrink the routed width beyond the task-dependent limit, or quality degrades

- Reinvest in expert diversity: use the savings to increase the number of experts and top-k—for improved accuracy

Results at Scale

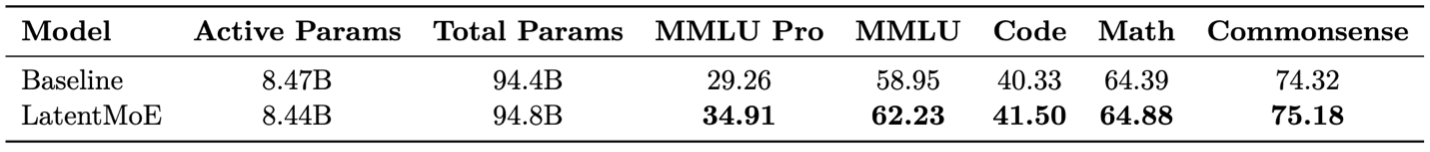

LatentMoE improves model accuracy over standard MoE baselines at similar serving cost—across both small and large scale (Table 1).

Table 1. LatentMoE vs. baseline on a 95BT-8BA Transformer MoE, showing higher accuracy across all tasks at equivalent parameters.

Table 1. LatentMoE vs. baseline on a 95BT-8BA Transformer MoE, showing higher accuracy across all tasks at equivalent parameters.

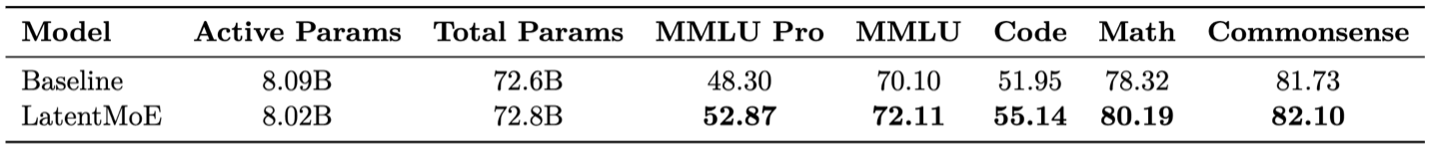

LatentMoE also generalizes beyond Transformers to hybrid Mamba-Attention MoEs (Table 2).

Table 2. LatentMoE vs. baseline on hybrid Mamba-Attention MoEs, showing higher accuracy at equivalent parameters.

Table 2. LatentMoE vs. baseline on hybrid Mamba-Attention MoEs, showing higher accuracy at equivalent parameters.

LatentMoE has been adopted in the flagship Nemotron-3 Super and Ultra models and scaled to longer token horizons and larger model sizes (see the Nemotron-3 white paper). Stay tuned for Super and Ultra model releases in the coming months.

Projected Serving Impact at Trillion-Parameter Scale

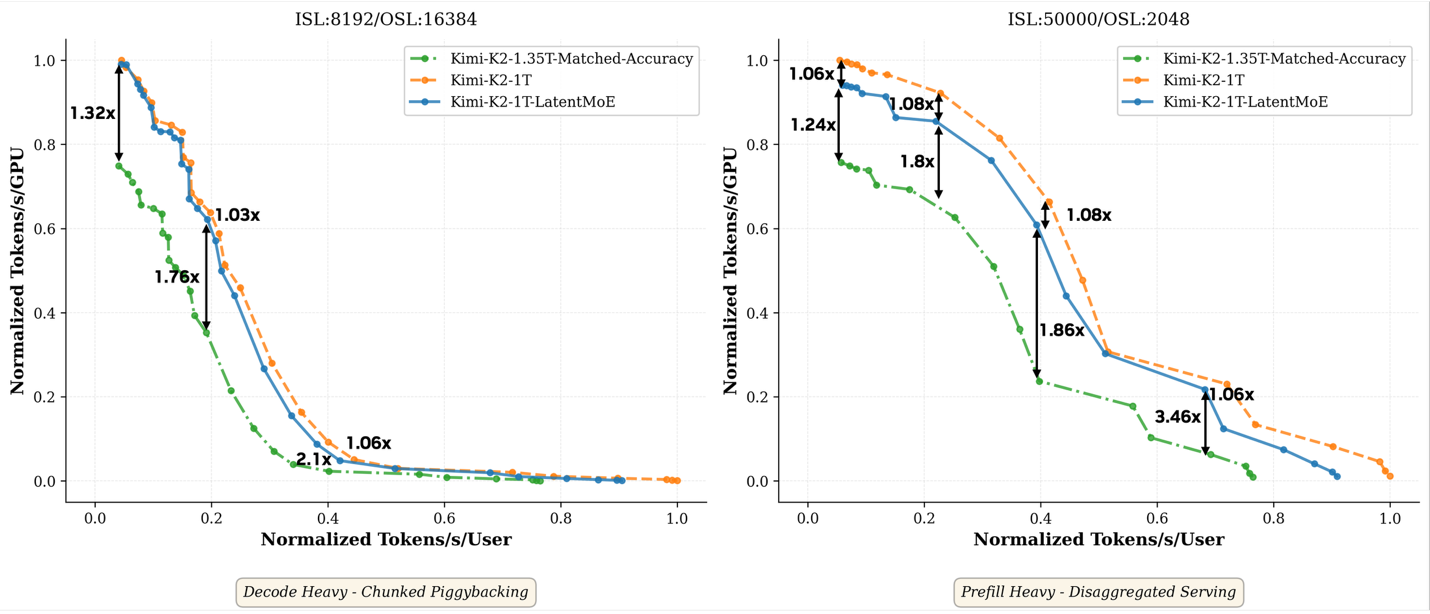

To connect architecture decisions to end-to-end serving, we project throughput-per-GPU and latency Pareto frontiers at trillion-parameter scale. The key comparison: if a standard MoE is scaled to match LatentMoE’s accuracy gain, it requires 350B additional parameters in our analysis. At iso-accuracy, LatentMoE is projected to achieve up to 3.5× speedup over standard MoE (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Normalized throughput–latency Pareto frontiers at trillion scale for decode-heavy and prefill-heavy regimes.

Figure 2. Normalized throughput–latency Pareto frontiers at trillion scale for decode-heavy and prefill-heavy regimes.

LatentMoE introduces two shared linear projections around the routed expert path: a down-projection before dispatch and an up-projection after combine. In our analysis, this added compute is modest (~9% relative to native Kimi-K2-1T) and far smaller than the cost of scaling a standard MoE to match accuracy.

Conclusion

Sparse compute isn’t automatically cheap at inference. MoE serving often pays in memory bandwidth and routing overhead, not just FLOPs. LatentMoE addresses this directly and pushes the accuracy-efficiency frontier beyond standard MoE baselines. We hope this work opens the door to more principled and scalable MoE designs.

For full details, see the paper.